Sharing rich media has never been more critical to delivering healthcare, nor has it been a greater risk.

As technologies evolve, they can assist clinicians in collaborating toward patient outcomes; however, capturing and sharing private patient information creates a notable security risk that must be mitigated.

This article continues our series of check-ups on key digital health topics for 2025.

“With most mobile phones and tablets equipped with high-quality cameras...it is easier than ever to capture and distribute clinical photos...care needs to be taken to ensure patient privacy, particularly when they are taken on a personal mobile device that belongs to the clinician and is used outside of the workplace.”

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners

As the RACGP identifies, mobile devices and tablets are enabling clinicians to create and share rich, detailed media in ways that have never been seen before. This creates opportunities for faster consultation and knowledge sharing, so patients receive the best care sooner.

Most clinicians have immediate access to one or more devices that can

- Take high-quality photos,

- Film high definition video,

- Record dictation or other audio, and

- Share those and any other files with third parties via a plethora of communication mediums.

These can then be further enhanced by clinical additions or unique applications of commercially available solutions, enabling the creation of portable and convenient biomedical imaging (or other recording) systems, leveraging the smartphone.

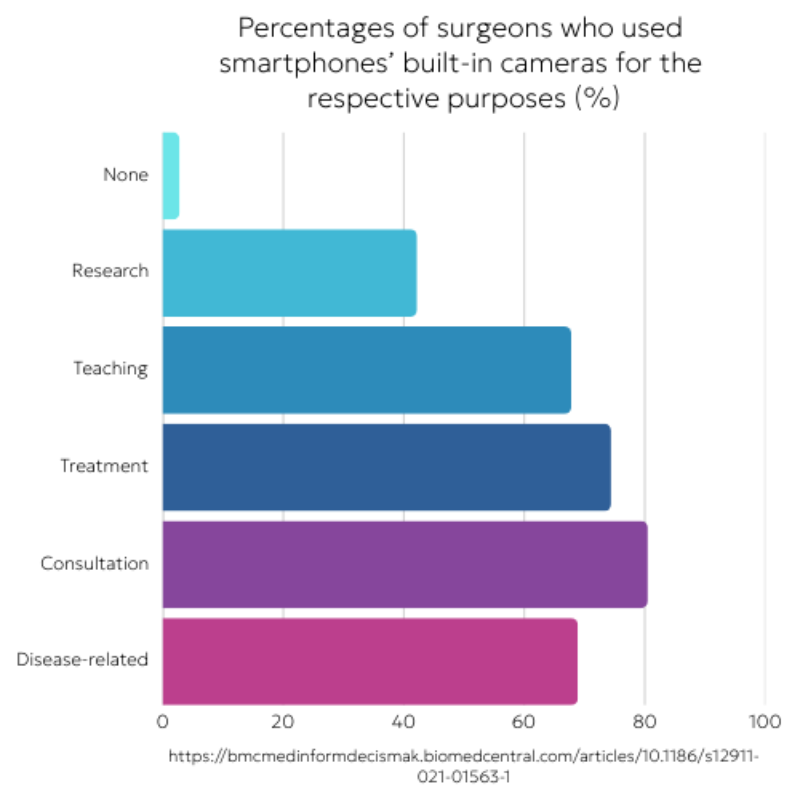

Clinicians are already taking advantage of this wealth of opportunities. A recent study of surgeons found that 99.5% were already using their smartphones for work purposes. Within this 70% were texting colleagues, and 60% were taking or viewing others’ photos or videos.

Smartphone use was found to occur in Emergency Departments, outpatient clinics, on wards, and even in the operating room.

These results were also stronger for doctors with more advanced computer skills and those earlier in their careers. This suggests that the clinical use of mobile devices is already well-established, making it ever less likely that this could be rolled back.

A separate examination of clinical photography highlighted dermatology and wound care as areas that consider photography, supported by smartphones, as a mandatory part of treatment referral. In emergency settings, it was found that timing and delivery of images were most important, further enhancing the relevance and reliance on the smartphone that almost every clinician can immediately access.

This drew the authors to the significant conclusion that guidelines for clinical use of smartphones are now required. If hospitals cannot feasibly prevent the use of mobile technologies, they must look to mitigate the risks and better leverage the available capabilities.

As hospitals seek to incorporate mobile phone use into their workflows, three clear themes of risk emerge: data security & information privacy, legal rights & data storage regulations, and assurance of patient consent. These are obviously interrelated, requiring hospitals and clinicians to have official guidelines, a firm understanding of these risks, and the tools to deliver best practice.

While the opportunities are immense, increasing the volume and complexity of patient information being captured and stored presents an increased risk to hospitals and other healthcare organisations.

A clinical photograph is sure to record sensitive information. The clinical setting confirms that the data is likely subject to health-specific regulations, and images or other records are usually of a patient’s person, intimate, and potentially embarrassing for adults, with even greater legal implications when considering minors.

When capturing or transferring images, we can see a variety of immediate risky scenarios:

- Sending data to the wrong recipient – an incorrect recent contact, typographical errors in contact numbers, outdated contacts with shared mailboxes, personnel with the same name, or just a message to the wrong number.

- Data being transferred may be intercepted. Private health information, especially imagery with the potential to cause psychological harm, presents an attractive target for bad actors.

- When capturing data, a record is always kept on the original device. The clinician takes a photo and sends it to a colleague for review. That file might be backed up to a private cloud system or mirrored when they manage their device, creating further copies of sensitive data.

- Even with good personal practices, the clinician has limited control over the receiver and how they secure their information. The data can again be backed up or copied far beyond the reach of the patient or their care provider.

When a messaging service is used, a copy of the data could be stored in a third-party repository. With global tech companies being the leading providers of such services, it could mean that patient photos aren’t even on either clinician’s phone but are archived in a data centre anywhere in the world.

Taking photos of someone using a mobile device constitutes processing personal data, which requires compliance with the Privacy Act 1988. This act sets out the Australian Privacy Principles (APPs).

These are further distilled into Health sector-specific applications of the law at a state level. For example, the NSW Health Privacy Principles (HPPs) instruct that

- Collection – Must be lawful, necessary, relevant, accurate, directly received from the patient to the healthcare organisation, with transparency into the data’s use.

- Storage – must be secure, kept no longer than is necessary, and protected against loss or unauthorised access and modification.

- Access & accuracy – must be available and able to be updated by the contact the information references, as well as offered transparency to the subject.

- Use – must be limited to the reason the data is collected.

- Disclosure – cannot be disclosed unless directly related, as the subject might expect, such as between care providers.

- Anonymity – can only be linked to the individual’s identity when necessary, including the provision of services anonymously where lawful and practicable.

- Transferrals & linkage – can only be shared within (in this case) NSW Health and recorded into systems with express consent.

It is clear here that when a clinician snaps a photo of a patient’s concern, there is a significant requirement on the healthcare organisation responsible for the patient to take on each of these responsibilities.

A clear starting point in discussions about clinical photography and other digital media is the subject's consent, a complex medicolegal topic.

When it comes to capturing and transferring rich media, the clinician must keep this in mind.

As the General Medical Council (UK) identifies, there are types of media where consent may be considered implicit, such as images or videos of internal organs and structures and media captured during laparoscopic or endoscopic procedures, for example. The GMC also highlights pathology slides, as well as other radiology recordings, including X-rays, CT scans, MRI images, and Ultrasound recordings. Additional parties often record these files and then share them with the treating physician.

For other scenarios, obtaining explicit consent would usually be required. That consent needs to be specific to the media being created, including informing the patient where the media could be transmitted. The GMC suggests good practice is to confirm consent in writing. Where that isn’t possible, they recommend verbal consent be noted in the appropriate documentation.

The clinician also needs to accommodate those who cannot explicitly consent – minors as well as adults without the capacity to have that discussion, by virtue of their condition or other impairments.

Once consent is established, the next issue is to utilise appropriate tools to ensure data is captured, transmitted and stored with adequate security measures. Implementing data management and privacy guidelines is crucial to mitigate the risks being created for the hospital, clinician and patient.

Authors in the BMJ recommended that the clinician’s device have a strong passcode, and (commercial) cloud backups should be disabled. Using a dedicated healthcare app for capturing images or other rich media with secure encryption is also recommended.

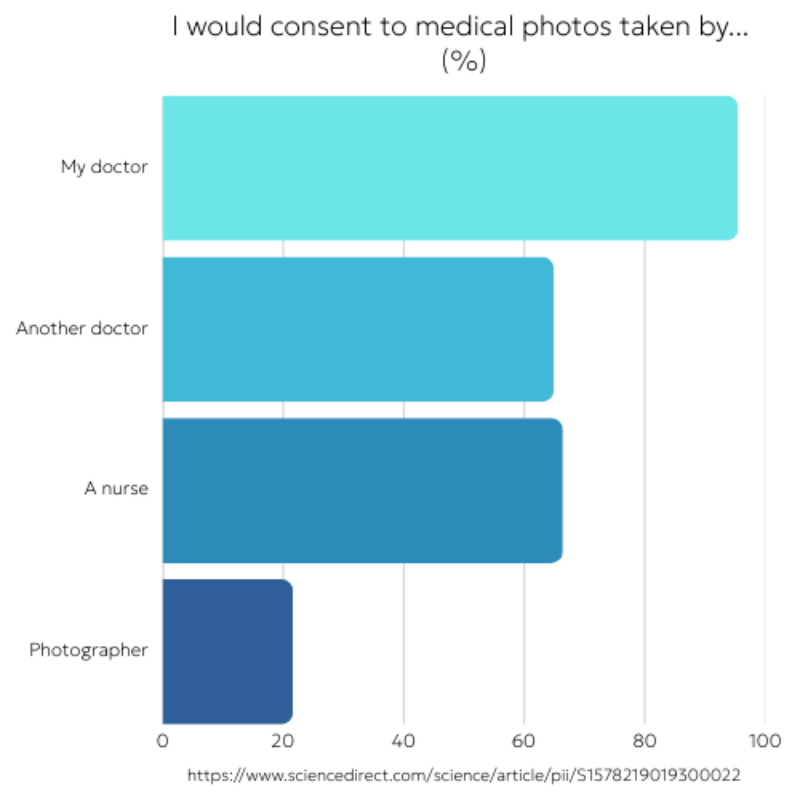

For recording devices, patients themselves may provide insight into what would be appropriate.

Studies of clinical photography research found the following:

- 94.8% of patients held a clearly positive opinion of medical photography in general. This included 88.1% approval of the use of subsequent treatment and 86.6% support for using photos for consultation with other physicians.

- The patients’ approval decreases with the personal sensitivity of the (physical) area being documented.

- 95.5% of patients prefer photography to be undertaken by their treating physician, decreasing to 66.4% when handed to a nurse or 64.9% if another doctor steps in. (Link)

- 81% of patients preferred to be photographed by their treating doctor, with 63.3% preferring the use of cameras owned by the facility.

- A substantial majority (92.8%) of patients approved of the clinical photos being included in case studies, and 90.3% in medical records. (Link)

- This level of acceptability is also not particularly recent. In a study conducted before the widespread adoption of smartphones, 98% of patients accepted having images captured by their doctor, 74% accepted sharing these images for consultation with other doctors, and 82% approved of their use in teaching, while 88% approved of their use for patient education. (Link)

- One key consideration in the photographic process is that a clear majority (78.8%) of patients in another survey felt that the consent form “should list all the possible uses of the images” (Link)

So how should clinical media be managed?

Clinical photography, and by extension any other rich media a clinician can capture, is now an integral part of practice. It is therefore essential for healthcare provider organisations to manage this properly by implementing safeguards and equipping their clinical teams with the knowledge and tools to use this securely and in a way that respects patients.

To summarise our findings, we have identified five key tasks for hospital decision-makers to address the benefits and risks of clinical media.

- Provide guidelines and instructions to assist clinicians in managing patient privacy and confidentiality.

- Establish and communicate secure facilities for taking, storing, and transmitting clinical media.

- Empower doctors to capture media themselves, to ensure the highest degree of patient comfort.

- Offer clear advice to patients about how and where any media might be used or transmitted.

- Take a proactive approach to recording patient consent, erring on the side of written authorisation, as early in treatment as possible.

How does Ikonix Technology handle rich media?

Creating clinical media.

To support healthcare delivery, we developed Ikonix Connect to natively manage complex media. Users can capture photos or videos and record voice notes. These, along with other file attachments, can be securely shared with other users.

Images or other items captured with the app are encrypted and stored only within the app, segregated from personal data, rather than on the general Camera Roll or gallery.

Additional security measures limit access to backups, and users can be remotely logged out if, for example, the phone is lost or stolen, as well as app-specific additional PIN lock.

Distributing content.

Importantly, data captured with the app itself is only shared with other personnel from the integrated directory. This means that data is encrypted on the original phone and then shared only with known and approved personnel within the organisation's directory, reducing the risk of accidental dissemination.

Data shared between collaborating clinicians is securely transmitted over a private network to prevent unwanted intrusion.

At an organisational level, records are stored encrypted but still auditable by suitably credentialled hospital leaders, ensuring quality of records, as well as ongoing security.

Device management.

Ikonix Connect caters to private/personal phones (BYOD), organisation-owned handsets assigned to an individual, or Shared Devices, where clinicians hand the phone between them to manage on-call responsibilities.

It's clear that patients prefer media to be captured using hospital infrastructure, but this obviously runs against the significant investment in providing handsets to all staff. It’s for this reason that Ikonix Technology has developed the security features inherent to the app, enabling clinicians to have an informed discussion about how and where the patient’s data will be transmitted, and deliver certainty for all parties.