Collaboration between clinicians is fundamental to patient-centred care in Australia’s modern healthcare system.

Innovations in communication technology have seen significant leaps forward in how clinicians collaborate within, and outside the hospital.

In this article we continue our series of check-up on topics in digital health in 2025.

“An interdisciplinary approach relies on health professionals from different disciplines...working collaboratively as a team. The most effective teams share responsibilities and promote role interdependence...

Communication across disciplines, care providers and with the patient and their family/carers, is essential...”

Department of Health, Victoria

'Improving Access' — an interdisciplinary approach to caring.

In previous articles we’ve discussed

- Critical Messaging – the dispatch of time-sensitive information, including finding the right recipient, and

- Interoperability – information moving between systems and along workflows, to deliver efficiency and patient benefit.

This article examines collaboration between clinicians, the types of collaboration that occur within treatment teams, and the barriers to collaboration that can occur in a healthcare setting.

As the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care identifies in clinical communication, collaboration can occur simultaneously, e.g. verbal communication between clinicians; or at different times, such as written communication of assessments and notes into a care plan read later by another clinician.

Key considerations are the elements of communication: the sender, receiver, the message itself, and the channel of communication used.

Why and how do clinicians collaborate?

It has further been identified, forming a consensus in the literature, that collaboration across disciplines in healthcare is associated with

- Increased patient safety,

- Lower rates of hospitalisation,

- Enhanced coordination of care,

- Reduced rates of complications and errors, and

- Improved patient access to medical services.

Three modes of collaboration are often discussed: multidisciplinary teams (MDT), interdisciplinary teams (IDT), and transdisciplinary teams (TDT). These are often discussed with some degree of interchangeability, but there is distinction between each mode.

Multidisciplinary teams:

Specialists from various fields working in parallel, each contributing their own assessments and treatments without deep integration, often coordinated by a lead clinician. This would be the case for patients with multiple but distinct requirements. In such cases what the patient needs from each team member, and the care plan role of each treating specialist, is clear.

Interdisciplinary teams:

Professionals from different disciplines working closely, sharing insights, and integrating their expertise to create a unified patient care plan. This becomes more collaborative and integrated when the patient has more complex, or more overlapping conditions, and conjoint efforts work toward a shared care plan goal.

Transdisciplinary teams:

Going further removing siloes, transdisciplinary team members cross traditional role boundaries, co-develop solutions, and share skills to provide holistic, patient-centred care. Roles become more ambiguous and significant trust and established relationships are usually required, with clinicians sometimes delivering the tasks that would otherwise have been done by different disciplines. This is the most involved and sometimes impractical to achieve.

Collaboration across disciplines enhances productivity, optimises the use of each member’s expertise, and fosters greater individual accountability toward shared goals.

This approach not only ensures comprehensive patient care but also sparks creativity, driving innovative solutions in treatment and care delivery. It is therefore important the healthcare organisations provide the capability for this to be conducted.

Communication policies and pathways and the underpinning infrastructure can be examined when the impacts are most important – in an emergency.

A recent CSIRO study on a Medical Emergency Team (MET) found

- Communication methods were not sufficient for clinicians’ requirements,

- Clinicians lack a “shared mental model” of shared responsibilities, and

- Improving care for “timely and appropriate management of patient deterioration” will require enhancements to communication infrastructure and interdisciplinary collaboration.

For non-healthcare readers’ clarity, per the Royal Children’s Hospital Melbourne, MET means the team of “specialised doctors and nurses which responds immediately to a call for urgent medical help”.

What are the barriers to collaboration across disciplines?

A study specifically into barriers identified the central or common theme of accessibility. This was described as having both a physical and a psychological dimension. From there a series of sub-themes were described – social norms, hierarchy, cognitive bias, and relationships.

Physical Accessibility.

This is the space in which the clinicians work and can interact – wards and theatres, meeting rooms and other common areas. This is further expanded to include influential factors such as rounding schedules. when clinicians are together for discussion. These schedules affect the perception of accessibility of colleagues and differ considerably based on the roles. That difference decreases the opportunities for interdisciplinary teams to collaborate at the patient’s bedside.

The study also identified the structural impact of “difficulty in identifying the appropriate individual to contact on the team requesting a consultation”. If a clinician does not know from whom they can get advice, the opportunity for collaboration decreases.

Psychological Accessibility.

A lack of ‘responsiveness’ was identified to be a key psychological barrier. When a colleague does not answer contacts or return calls, texts or pages, it prevents collaboration between disciplines.

Different teams have different ‘mental models’ of the responsiveness required of them, and those reaching out interpreting the (lack of) response as a gauge of the consultant’s willingness, while the responder can perceive inbound requests to be asking them to be a ‘technician’ rather than provide clinical expertise. The discrepancy between these creates a psychological barrier to accessibility for the consultation, on both sides of that contact.

Social norms.

The same study describes these as ranging from ‘unspoken conventions’ to vastly different management protocols utilised between disciplines. Both sides can impact the capacity for collaboration as clinicians have different understandings of actions to be undertaken, even for the same patient situation, starting from different default positions, and without a process of shared clarification.

Hierarchy.

Explicit or inferred hierarchical disparities can impede collaboration as they can guide expectations of who should be contacted, and how information should be shared. As information passes through more stages it can change in meaning, or it might not be passed along in a timely manner. If clinicians forward a message regarding patient deterioration to their equivalent hierarchical level in another discipline, for it to then be passed upward, the update may never reach the leader, and miss achieving the intended patient outcome.

Cognitive biases.

These are the biased expectations of the other clinician. In this setting that could be by demographic characteristics, or judgements regarding discipline or career stage. The collaboration impact, positive or negative, comes from these predeterminations, expectations informed by attributes unrelated to actual professional capability.

Relationships.

These can again impact both positively and negatively. Prior exposure and successful collaboration facilitate future interdisciplinary contact. This can include activities not patient specific, such as committee and panels, or outside conferences. The authors note that mutual respect and feeling heard in working relationships is key to accessibility and interdisciplinary communication.

Clinical collaboration is at the heart of the Ikonix Unified Messaging Suite.

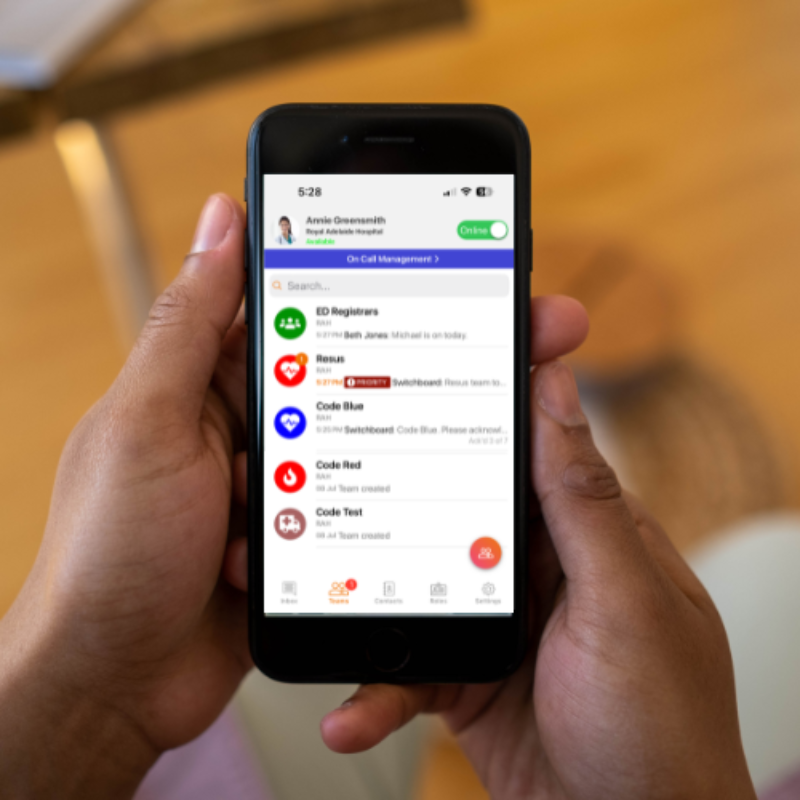

Collaborate in a Secure Group Chat

Enabling clinical collaboration at its most elementary means providing a space for discussions to occur. With clinicians on the move and working across different shifts, this is best achieved by facilitating the virtual meeting room of a simple group chat.

The complexity for healthcare comes in the need for security. From our experience developing Ikonix Connect we understand that the consumer-grade chat solutions with which many of us are familiar need a secure clinical equivalent, or clinicians will made do with consumer apps to facilitate communication.

Implementing a system such as Ikonix Connect not only offers the directory integration and role-based messaging features built for healthcare, but also the encryption suitable to ensure patient privacy.

Role-based communication.

Finding with whom to collaborate is one of the first struggles for care teams. With role-based messaging clinicians can find the on-call, available specialist in the Role for consultation and information, without knowing in advance who the individual might be.

Directory integration.

By placing the entire directory in the palm of the hand, clinicians can access any specialist they need, searching the hospital, network or the entire health system for the right advice or consultation.

Complete messaging.

Within the IUMS, clinicians can utilise any available mechanism to make contact. This could include voice or video calling inside a collaboration app, sending pager messages, or broadcasting information to a fixed display with Ikonix Billboard.

Message acknowledgement.

Collaboration need not always be detailed back and forth. Inside Ikonix Connect clinicians can request a quick acknowledgement or an accept/decline response – alert colleagues to a task and ensure someone confirms they can get it done.